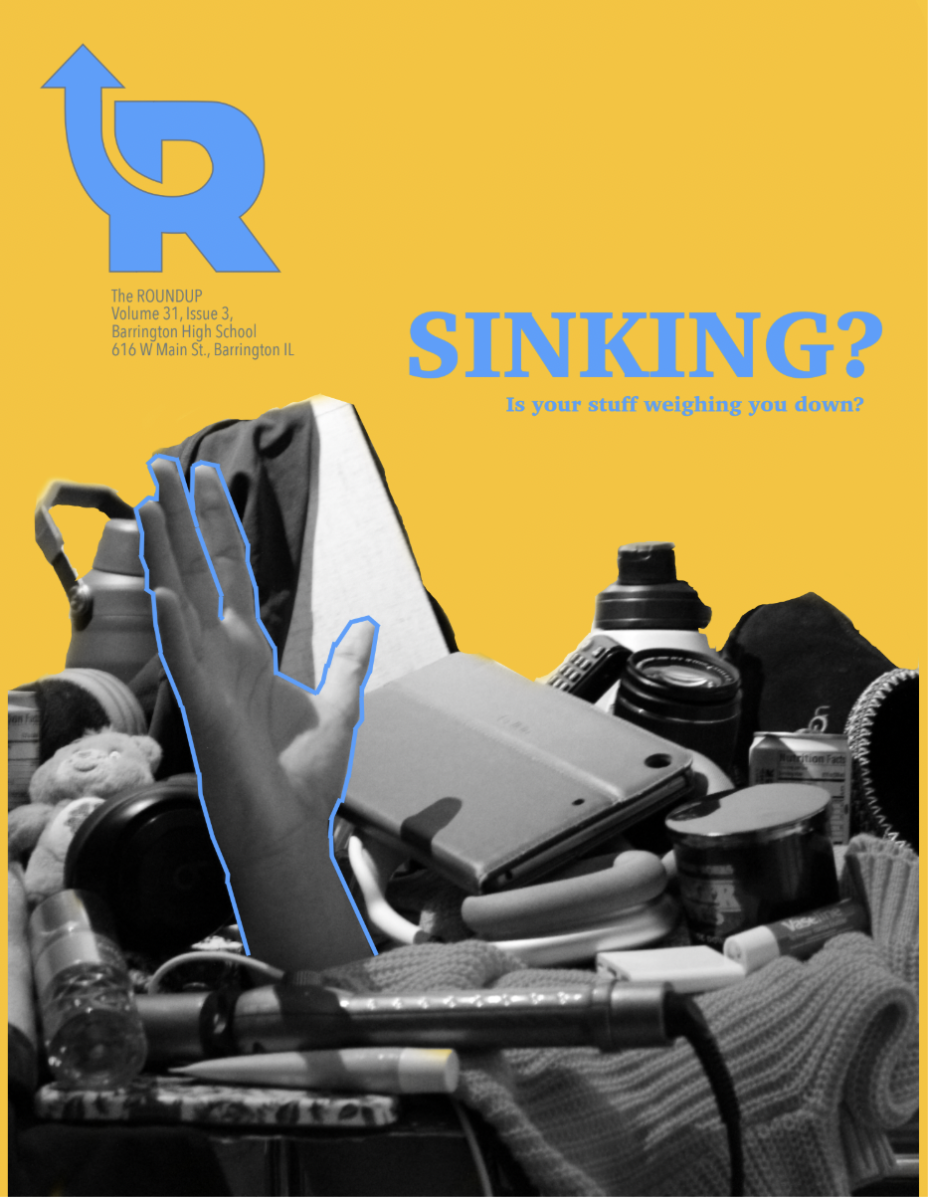

What’s behind the uniform

George Balanchine, the founder of the New York City Ballet, first popularized the ideal of the “Balanchine Ballerina” in the 1960s: a long-legged, extremely thin girl with a short torso, small rib cage, long neck and small hips. After Balanchine, this aesthetic became a reality as companies and schools began to select girls that met the specific criteria. For example, Vaganova Ballet Academy in Russia has a table of height and weights that their students are required to meet. If a girl weighs over 110 pounds, regardless of height, she is not allowed to participate in pas de deux class.

Many dancers are aware of the physical ideals of ballet, some of which cannot be controlled, like one’s proportions. It’s not only about being skinny. The length of one’s legs compared to their torso, the natural flexibility of their feet and the amount of turnout a dancer possesses are sources of insecurity. Senior Lauren Chon, who has been dancing for fourteen years, has a clear image of the characteristics of a “ballet body.”

“I think that the ballet body is definitely on the leaner side. I have seen some dancers that are not as traditionally thin nowadays, but it’s still a fit physique. Specifically, Russian-style ballets care the most about the body, with the longer legs and the shorter torso,” Lauren said.

Just being conscious about one’s body shape is enough to generate self-criticism. Lauren’s sister, sophomore Morgan Chon, has been dancing for twelve years, and shares some of her own insecurities.

“I have bow-legged legs. When I’m in the first position, my knees don’t touch, and that for sure makes it tough. I’m working all my leg muscles, but my teachers are like, ‘Morgan, you’re being a lazy dancer, you need to stretch your legs,’” Morgan said. “What I’ve started to do is pull my leotard up over my hip bones, which is something I’ve done for the past few years, when I’ve become really self-conscious about the way I looked in a leotard, because it makes my legs look longer.”

Morgan is not alone. According to a study conducted by Ofra Walter of Tel-Hai College, female ballet dancers are “more preoccupied with weight, eating habits and body image.” These unhealthy fixations can cause more serious issues. The Washington Post reported that one out of two ballet dancers suffers from an eating disorder, which can develop as early as twelve years old.

“Since ballet is about how the position looks on you, and the clothes are very tight, you’re constantly looking in the mirror and being critical. Ballet is a really critical sport because you have to do it right and look perfect doing it. As a dancer, you have to be super critical of yourself to get anywhere,” Lauren said.

Freshman Molly Knecht, who has been dancing for almost twelve years, feels the pressure to perform perfectly during class.

“It’s really hard when you’re just in dance class, in just a leotard and tights, and there’s a mirror there all day. You have to perfect everything. Sometimes I think I would look more perfect if I looked like someone else,” Knecht said.

Knecht is attending the A&A Ballet Conservatory in Chicago next year. However, as the school is Russian-based, the pressure to meet the ideals is more present.

“Russian dancers are usually really tall and thin. It’s hard to think about it sometimes,” she said.

Sometimes the thought of comparison affects confidence in performance, both in the studio and on-stage. In most ballets, the majority of the dancers dance in the corps de ballet. The corps is expected to dance as one unit, with each member doing the exact same steps at the exact same time.

“I hate people watching me for shows, so I only have one or two of my closest friends come. It’s how you compare against everyone else, especially since my studio doesn’t do a lot of solos,” Lauren said. “Growing up, you’re all together in a line, and you all have to do the exact same thing and do it identically. I feel like that’s the pressure that makes me uncomfortable with people watching me.”

During the actual performances, Morgan is too busy thinking about the correct steps and the quality of her dancing to worry about her body. In rehearsals, however, the negative thoughts persist.

“When you don’t have that fancy tutu to cover up whatever you don’t like about yourself, and the rest of the people in that cast who aren’t dancing are watching you, that is so nerve-wracking,” she said.

However, the ballet world has come a long way since the 1960s. With the rise of ballet companies, such as the National Ballet of Canada, emphasizing diversity in their dancers, the idea the tall, thin and lithe ballerina is slowly disappearing in the professional realm. Ballerinas, such as Misty Copeland and Sara Mearns do not fit the traditional mold, but have achieved great roles in their careers. The success of these ballerinas is a source of motivation for young dancers everywhere.

“If I’m looking through Pointe Magazine, I realize that those dancers actually made it, and they don’t have the ‘perfect ballerina body’ that you’ve always heard of,” Knecht said. “It’s comforting to see that, and I just remember that if they can do it, I can do it. The ballet world has become more accepting of different bodies. It’s not just the Russian ideal everywhere.”

Above all, ballet is an art form. The movement of the dancers on stage and the beauty they emote is not limited to what their natural capabilities, rather the artistry they have cultivated during years of focus and diligence. Ballet is about more than someone’s body.

“I think that all of us can do stuff in class that is beautiful, and it doesn’t matter what shape you are. It doesn’t matter if you’re tall, short, or thin. I think that dance can make anyone beautiful,” Lauren said.

Your donation will support the student journalists at Barrington High School! Your contribution will allow us to produce our publication and cover our annual website hosting costs.