There is no ethical reason not to vote

You have the power to decide on the quality of life you want for yourself and future generations. Voting is your chance to stand up for the issues you care about like public transportation, raising minimum wage, or funding local schools. This is your life: take the time to help decide what’s best; vote on November 3. Many obstacles prevent citizens from voting, such as uncertainty about how to register or inability to get to the polls. But there is a subset of nonvoters who make a conscious choice not to vote for ethical reasons.

The three most common reasons I hear are: “I don’t have enough information,” “I don’t like any of the candidates,” and “I don’t want to give this election legitimacy.” I thought to myself that it is worth examining why each argument is flawed.

1. Lack of information

According to a recent study by the 100 Million Project, nonvoters are twice as likely as active voters to say they do not feel they have enough information about candidates and issues to decide how to vote. This group of nonvoters might believe that it is unethical to vote because they are uninformed. In “The Ethics of Voting,” political philosopher Jason Brennan argues that uninformed citizens have an ethical obligation not to cast votes, because their uninformed votes can produce results that damage our political system.

The honesty of this group of nonvoters is praiseworthy, especially in comparison with overconfident voters who suffer from what psychologists call the “Dunning-Kruger effect” and wrongly believe that they are better informed than they are.

Information about each candidate’s platform is more accessible than ever. It can be found online, in print and through conversation. The problem today is instead how to find reliable, nonpartisan information. One of the clear benefits of mail-in voting is that it gives voters more time to fill out their ballot carefully without feeling rushed. While completing the ballot at home, they can educate themselves about each of the candidates and issues.

2. Dislike of the candidates

Another common reason for not voting is dislike of the candidates. In fact, a Pew Research study found that 25% of registered nonvoters did not vote in the 2016 election because of a “dislike of the candidates or campaign issues.” Based on their dislike of both candidates, they found themselves unable to vote for either one in good conscience.

What this leaves open, however, is the question of where this “dislike” comes from. It is quite possibly the product of negative campaigning, which promotes negative attitudes toward the opposing candidate. If you already dislike one party’s candidate, negative ads encourage an equally negative feeling toward the other party’s candidate. This suggests that negative campaign advertising carries out a strategy to depress overall voter turnout by making voters dislike both candidates.

But dislike is not a sufficient reason for abstaining. The mistake here, I believe, is that choices are not always between a positive and negative, a good and a bad. Voters often have to choose between two good or two bad options. It’s also worth noting that, in addition to the top of the ticket, there are often important state and local contests on the ballot.

Finding just one candidate or policy proposal that you truly support can make the effort to vote worthwhile. State and local races are sometimes very close, so each vote really can be meaningful.

3. Contributing to a corrupt system

Two common reasons given for not voting are the attitudes that “their vote doesn’t matter” and that “the political system is corrupt,” which together account for about 20% of the nonvoting population, according to the 100 Million Project’s survey of nonvoters. Voter turnout is often interpreted as a sign of public support that establishes political legitimacy. By abstaining, some nonvoters might see themselves as opting out from a corrupt system that produces illegitimate results.

This way of thinking might be justified in an authoritarian regime, for example, which occasionally holds fake elections to demonstrate popular support. In such a society, abstaining from voting might make a legitimate point about the absence of open and fair elections. But a 2019 report ranks the U.S. as the 25th most democratic country, classifying it as a “flawed democracy” but a democracy nonetheless. If democratic elections are legitimate and their results are respected, voter abstention in the U.S. has no practical impact that would distinguish it from voter apathy.

All three of the above arguments fail, in my opinion, because they measure the worth of voting primarily in terms of its results. Voting may or may not yield the outcome individuals want, but without it, there is no democratic society.

However, in the current context of the pandemic, there is one valid ethical reason for not voting, at least not in person.

On Election Day, if you are diagnosed with COVID-19 or have similar symptoms or are quarantined, then you should certainly not show up to the polls. The good of your vote will be outweighed by the potential harm of exposing other voters to the virus. Of course, as individuals we cannot know now whether we will find ourselves in that position on Election Day. But as a society we can predict that a significant percentage of the population will find themselves precisely in that situation at that time.

Knowing this will happen, voters need to adopt what ethicists call “the precautionary principle.” This principle says people should take steps to avoid or reduce harm to others, such as risking their life or health.

Based on the precautionary principle, an ethicist could argue that individuals ought to request absentee ballots, if their state provides this option. And in turn, the precautionary principle requires that each state should make absentee or mail-in ballots available to all registered voters. We should protect ourselves and all other citizens from having to choose between their health and their voting rights.

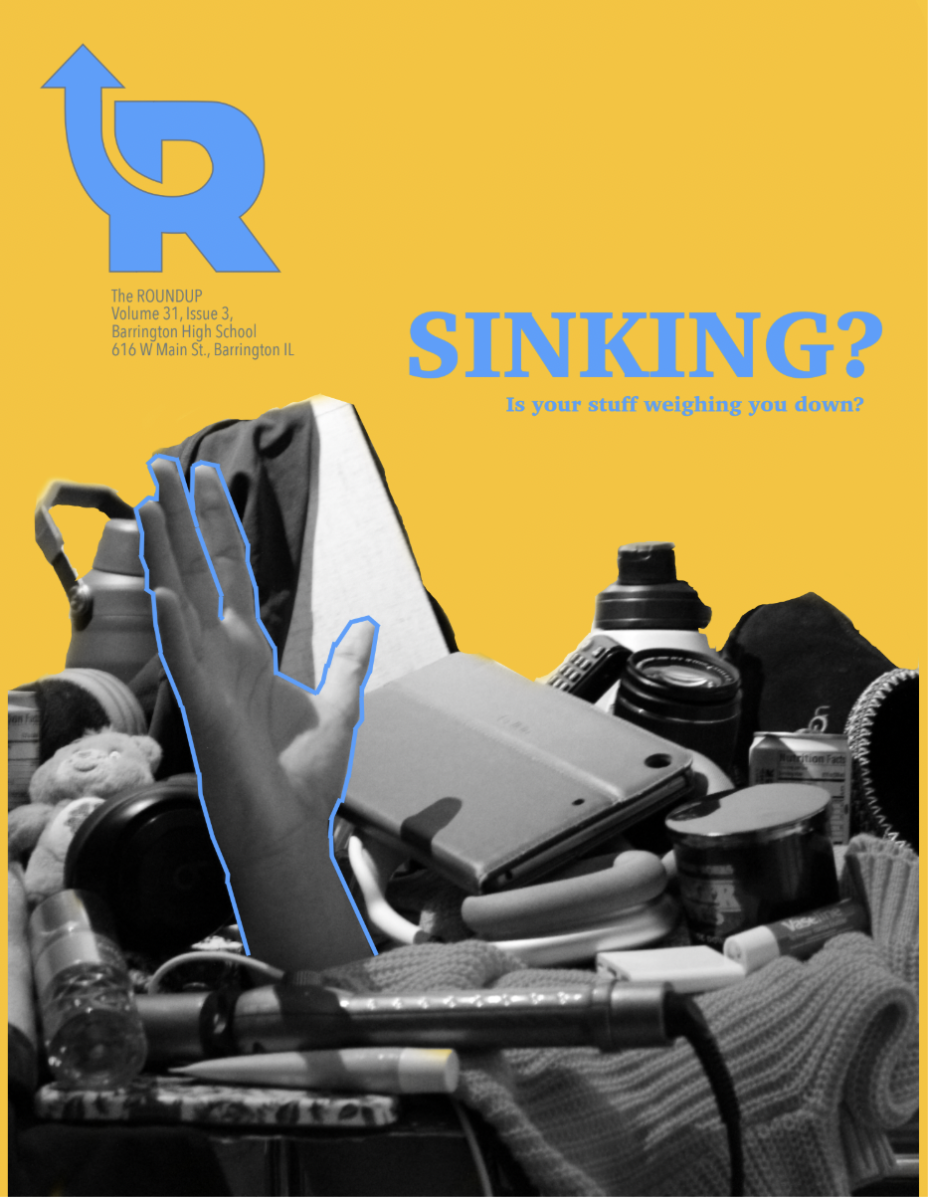

Your donation will support the student journalists at Barrington High School! Your contribution will allow us to produce our publication and cover our annual website hosting costs.