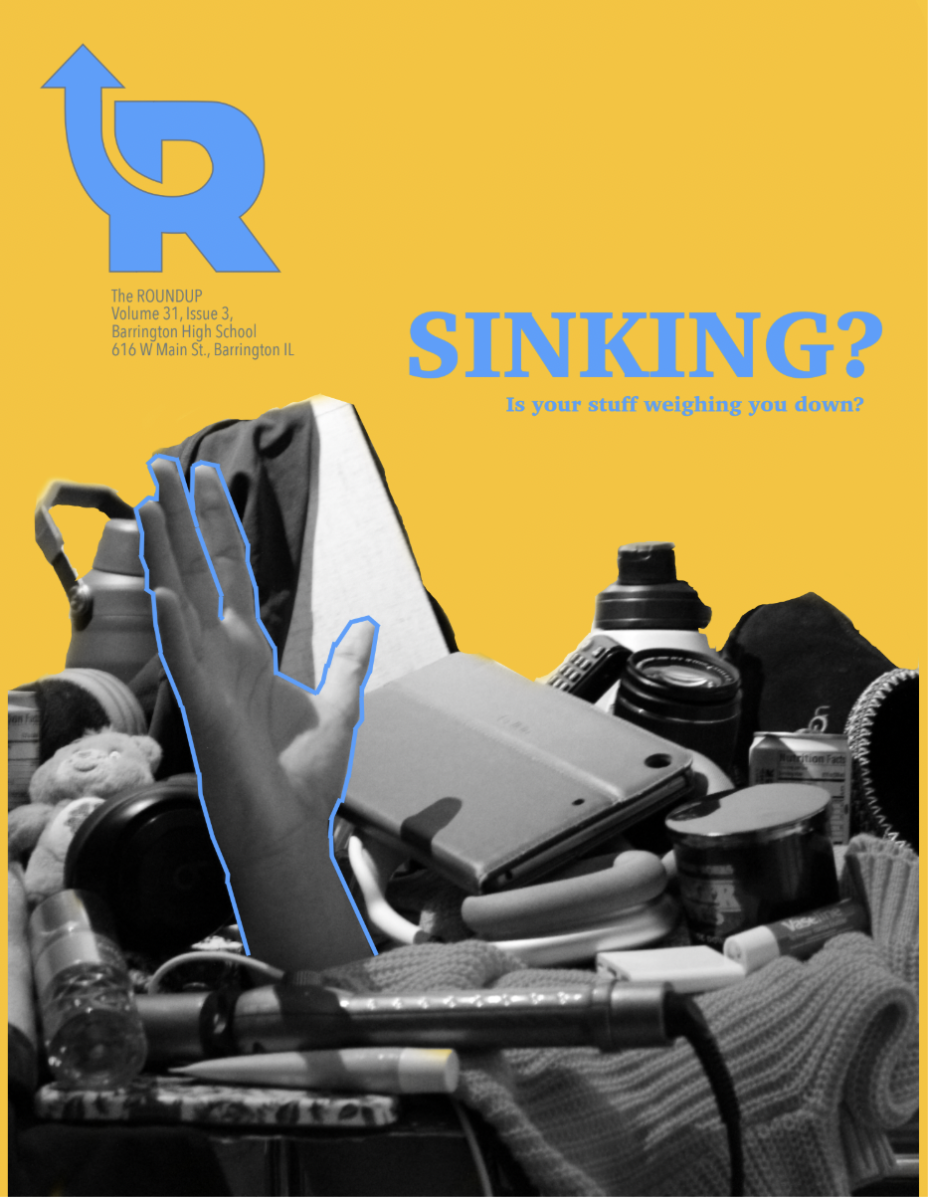

“Yes” is a word often used to agree, or give consent, to something. But what happens when it’s not freely given? And how do you know the difference?

“Sometimes people don’t even realize that what happened counts as assault,” BHS guidance counselor Allie Bauer said. “They’re like…‘I kind of wanted to, but then I didn’t — but I ended up saying yes.’ That’s not okay. That’s assault.”

This stands in contrast to the beliefs of a majority of BHS students. When asked in a survey to rank how informed they were on topics related to sexual violence, most students seemed to believe that they wouldn’t fall into such a trap. Identifying what counts as sexual violence and what is/isn’t consent were the top two topics that students said they were most informed on. So what’s not clicking?

What do you know?

The issue may be a case of people not knowing what they don’t know. Most students are familiar with the yearly Erin’s Law presentation provided by BHS, which covers the basics of identification, prevention and recovery. Notably, it provides students with important information about consent and red flags. Additionally, 91% of the students who were surveyed also said that they had learned about sexual violence outside of Erin’s Law. But despite the many resources out there, some things still seem to be slipping through the cracks.

Students have voiced the difficulties in identifying types of sexual violence. In the same survey, a majority of responses indicated that the difference between sexual assault, harassment, and abuse specifically was a topic they were less informed on. Yet, according to RAINN (the Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network), “one in nine girls and one in 20 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault.”

In the same survey of over 60 BHS students, 48% — almost half of the respondents — said that they knew at least one survivor of sexual violence. While some of the respondents may be talking about the same people, they may also know more than one survivor.

“The minute that someone says ‘No,’ ‘Don't,’ or ‘Stop,’ that goes from a consensual act to a non-consensual act. And it's assault,” Bauer said. “Sometimes people are like ‘I said yes’ — but you can take that back. I think that that's one of the things that I don't think that students always understand.”

The specific type of assault that Bauer is describing is sexual coercion. Planned Parenthood (a global nonprofit organization that provides sexual health care) defines sexual coercion as “...using pressure or influence to get someone to agree to sex…knowingly…or unknowingly, such as assuming the other person is OK when they’re not.” Coercion is one of multiple types of sexual violence that can occur, but — as Bauer noted — may be harder to spot.

Aside from knowing the different types of sexual violence that can occur, it may take time to realize that something was sexual violence or assault. According to ReachOut, an online, anonymous and confidential youth mental health wellbeing service, “it’s completely normal for it to take weeks, months or even years to recognise [sic] that a past experience was sexual assault.” ReachOut explains that the reasons for this can vary. Because sexual assault is a form of trauma, people may struggle with accepting what happened, or find it difficult to remember. Lastly, people sometimes don’t realize that what happened was assault until after the fact, which brings us back to Bauer’s point.

Why do these misconceptions still exist?

The problem isn’t that students don’t learn about Erin’s Law or Sex-Ed. Both are required by the state of Illinois and, as sophomore Lahari Beeram confirms, are taught each year. Despite COVID interrupting her health curriculum in seventh grade, her eighth grade health class picked up the topic again, and she was given an Erin’s Law presentation as a freshman in addition to taking health online over the summer.

The Erin’s Law presentation is given to students every year (save for sophomore year) when students are required to take health.

“There’s a whole unit for human sexuality…that addresses Erin’s law specifically…typically it's three days to a week spent on that information,” Stephanie Naumowicz, a health teacher at BHS, said.

If students choose to take health education over the summer (as Lahari and 120 other students did last year), they’ll do so online with Illinois Virtual School (IVS), which is also required by the state to cover the same material.

Our in-person health classes offer students an in-depth understanding of the topic. “We…bring in guest speakers…I think sometimes having an outside voice and an outside perspective can be helpful too…having someone that does have that freedom of speech and kind of opens up the room in a way that…nothing's off limits, and they might be able to relate to those individuals a little bit more,” Naumowicz said.

While BHS’s in-person health classes give students a chance to learn from a guest speaker, the IVS curriculum does not. Because it’s online, the learning material consists solely of articles that students will read to learn from, and assignments and tests to evaluate their understanding. The online classes meet state standards but lack the student engagement element that our in-person classes bring to the table.

“Honestly, the only thing that stuck with me and that was reiterated across the entire course was…to go to a trusted adult and consent…many people in various situations can’t give consent, and even if they were to, it doesn’t count,” Beeram said. “I remember these things because they were reiterated throughout…the entire course.”

These things that do stick are key to remember — but what about the things that don’t stick?

“I don’t really remember the other things because they weren’t reiterated that much. There was just a brief lesson and then we moved on. There was definitely a lot of confusion,” Beeram said.

Namowicz also shares this concern.

“I think sometimes by the time that students are juniors or seniors they might be a little bit withdrawn from the health content…and they might have forgotten some things with it,” she said.

Namowicz and Bauer also point out media as a potential cause for creating misunderstandings. “I feel like I've just been hearing especially this school year, about the casualness of hooking up…that lack of connection and commitment in a relationship where sex is involved can kind of trend towards misunderstandings,” Bauer said. “And like, yes, it's consensual, but at the same time, is this really what we want to be doing? Or is this what media and TV tell us is okay?”

“I think the biggest thing is the naivety that teenagers might have that's like, ‘well, that doesn't count’ or ‘that would never happen to me’. And just not necessarily realizing what it is really, and taking a closer look at like this is not okay, and this is okay. What we see in media, and society oftentimes, blurs those lines too,” Namowicz said.

The narratives depicted by TV shows and other forms of media, combined with students forgetting or feeling more withdrawn from learning about content related to sexual violence continue to add to the general confusion. Additionally, it may be what leads to the situation Bauer describes at the start of this article and the naiveness (as Namowicz puts it) that we have about the issue.

Survivor treatment

“When it comes to assault, it's it's really important that the person who was assaulted is the person that controls what happens next,” Bauer said. "Sexual assault is still like a pretty taboo topic that we might avoid talking about. But I think it's important that we do.”

A decrease mental health also tends to follow after surviving sexual assault. Depression, anxiety, and eating disorders are among the most common. Guilt, shame, and self-blame are also common after experiencing any form of sexual violence.

“There is a lot of work that needs to be done around the feelings of personal guilt. Like thinking ‘maybe I did something to deserve this,’” Bauer said. “The answer's no. There's nothing that you could ever do where you would deserve this happening to you.”

If you’ve been affected by issues raised in this story, information and support is below.

Available Resources:

After Assault

- WINGS Program (847-221-5680; 24⁄7)

- Kenneth Young Center (650 E. Algonquin Rd., Suite 104, Schaumburg, IL 60173; 847.496.5939)

- Mental health and medical services

- Northwest CASA

- KanWin

- BHS Wellness Center

Identifying Sexual Violence and Consent