For many teens, hair is more than just appearance—it’s personal. It’s the silent billboard of identity, culture, and sometimes, insecurity. Whether it’s curls, color, or texture, hair can carry a weight far heavier than its strands.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately—how something we can’t control can shape so much of how we see ourselves. For me, the journey started early. I have curly hair, the kind that frizzes in humidity and grows bigger by the second. Growing up, I spent years trying to make it behave. I straightened it, slicked it down, and kept it tucked away in tight styles that made it easier to blend in. I didn’t realize then that what I was really trying to smooth over was a sense of not fitting in.

But this story isn’t just mine. I’ve been speaking with others whose hair shaped their experience in ways both visible and invisible.

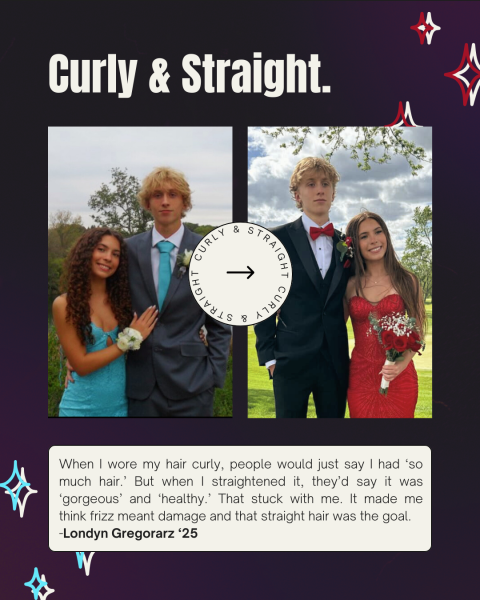

Londyn Gregorarz, a fellow senior, remembers feeling most different around fifth grade. “I had no idea what to do with my hair and wouldn’t let my mom style it, so it was stuck in a ponytail most days,” she said. “I was obsessed with straight blonde hair because it looked so good in pigtails or braids. My hair would just look stiff or ratty by the end of the day.”

For Londyn, comments from peers weren’t always cruel—but they were telling. “When I wore my hair curly, people would just say I had ‘so much hair.’ But when I straightened it, they’d say it was ‘gorgeous’ and ‘healthy.’ That stuck with me. It made me think frizz meant damage and that straight hair was the goal.” Even unspoken signals had an impact. “When girls would ask for a hairbrush, I’d just stare. You can’t brush curly hair dry—it doesn’t work that way.”

Her experience reflects a wider pressure among teens to meet often unrealistic beauty standards. According to a recent study, 51% of teens report feeling pressure to present themselves a certain way, including conforming to beauty trends and idealized hairstyles (Futurity.org, 2024). And 72% of girls say they feel pressure to be beautiful (Dove Real Beauty Research, 2023).

Special occasions brought more pressure. “I’d look back at photos and feel messy or out of place when I wore my natural hair. Everyone else’s hair fell neatly into place, and mine didn’t. So I straightened it for every event.” That began to shift during her junior year, when she wore her curls to homecoming and finally felt beautiful doing it.

Support came gradually, through family and social media. “Seeing old pictures of my mom and dad with their natural curls helped me realize what I could grow into. And during COVID, I started researching curly hair routines online. It still takes trial and error, but finding products and people who understand curly hair changed everything.”

Londyn’s turn to social media mirrors a trend: 60% of teens say they feel pressure to look perfect online, and 47% of teen girls admit to curating their photos to meet appearance standards (Standard Media, 2023; World Metrics, 2024). For those with curly or textured hair, that often means investing time, money, and emotional energy to manage a look that feels socially acceptable.

Now, Londyn sees her hair as central to how people know her. “My hair is part of my identity. When people think of me, they think of the confidence I have in myself—and in my curls.”

Her experience reflects something many students with unique features face: when difference becomes spotlighted rather than celebrated, it can lead to a subtle form of exclusion. Still, by embracing the very traits that once made her feel out of place, Londyn found a new kind of strength—and helped others see beauty in something real.

Her experience reflects something many students with unique features face: when difference becomes spotlighted rather than celebrated, it can lead to a subtle form of exclusion. Still, by embracing the very traits that once made her feel out of place, Londyn found a new kind of strength—and helped others see beauty in something real.

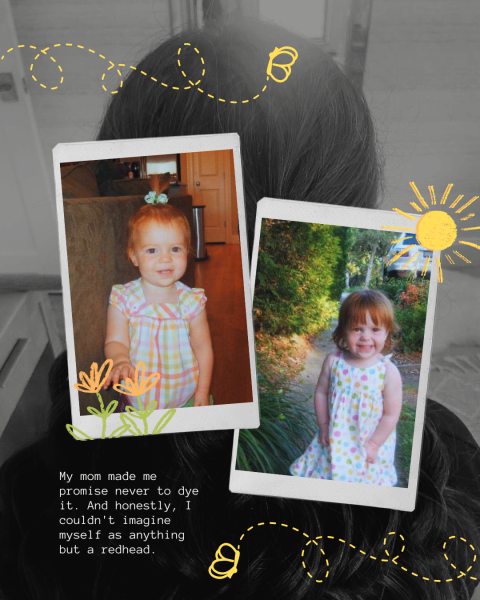

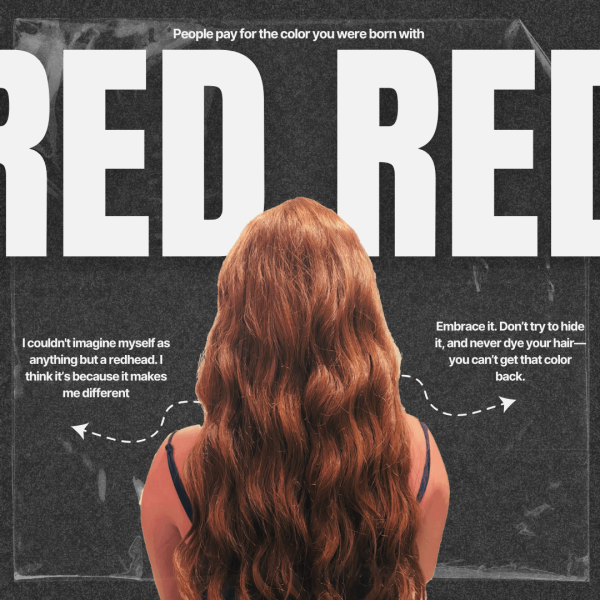

Lily Williams, another senior, knows what it feels like to stand out—sometimes too much. “I always think about gym class in elementary school. They would make teams based on hair color, and I’d be all alone. Like, ‘Okay, blondes, you’re a team.’ And there I was—just me.” This rarity is not just a personal experience for Lily—it’s statistically significant. According to the National Institutes of Health, only 1 to 2 percent of people globally have natural red hair.

Red hair became a kind of marker, not just of how she looked, but of how others saw her. “People would make ginger jokes. And I mean, if it’s original and funny, I’ll laugh. But it got old. It was always about being different. That’s what stuck with me.”

Though teachers were usually mature about it, peers often weren’t. “Kids would make jokes and stuff they thought were funny. It didn’t hurt me deeply, but it was annoying. Just constant reminders that I stood out.”

For a long time, Lily wished she could change her hair—but not entirely by choice. “My mom made me promise never to dye it. And honestly, I couldn’t imagine myself as anything but a redhead. I think it’s because it makes me different.” Red hair is caused by a genetic mutation in the MC1R gene, which is recessive, meaning both parents must carry the gene for the child to inherit it, even if neither parent has red hair themselves, according to Cleveland Clinic.

As she got older, that difference started to feel more like a strength. “I used to hate it. I didn’t like that kids were picking on me or making jokes. But now I think it’s cool. I’ve found what works for me, and I really like it. Sure, I can’t wear red or pink or orange, but I’ve figured out my style. I love it now.”

Public reactions helped shift her mindset. “Literally anytime I’m walking down the street, someone says something like, ‘Oh my gosh, your hair—people pay for that color.” While red hair remains rare, its unique appeal is clear. L’Oréal’s 2023 Global Hair Trends Report points out that red hair dye is one of the most requested colors in salons, despite the small number of natural redheads in the population.

Like many teens, Lily also searched for someone she looked like. “I always struggled to find a doppelganger. But I love gingers. Honestly, I’ve never met an ugly ginger—that helps me feel better about myself.”

Now, she would tell her younger self: “You’re beautiful. People pick on you because they’re jealous. Being different is good. Standing out is important. If everyone’s the same, it’s boring. I’m not boring.”

And her advice for other young redheads? “Embrace it. Don’t try to hide it, and never dye your hair—you can’t get that color back.”

Hair might seem like a shallow topic at first glance, but underneath lies a deeper question: how much of our self-worth is tangled up in how others see us?

For some, hair is a source of confidence. For others, it’s been a reason to feel left out. But across all of the stories I’ve heard and lived, one thing becomes clear—accepting your hair often parallels accepting yourself. And that journey, no matter where it starts, deserves to be heard.

A Celebration of Hair Stories

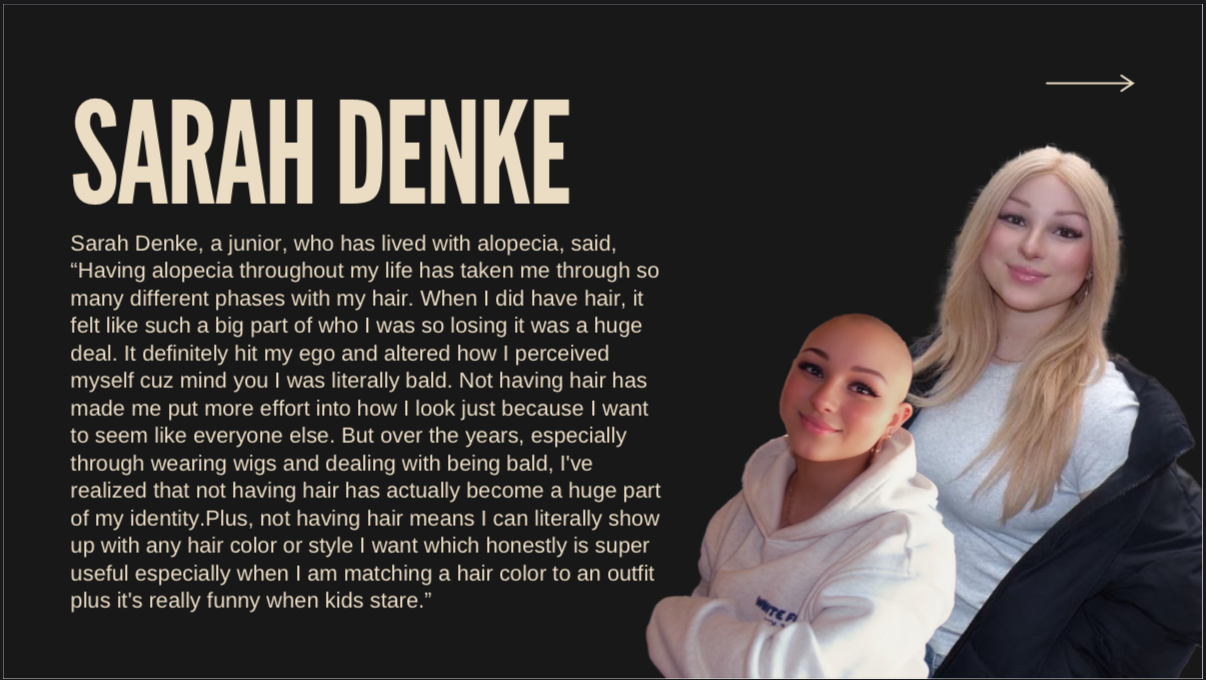

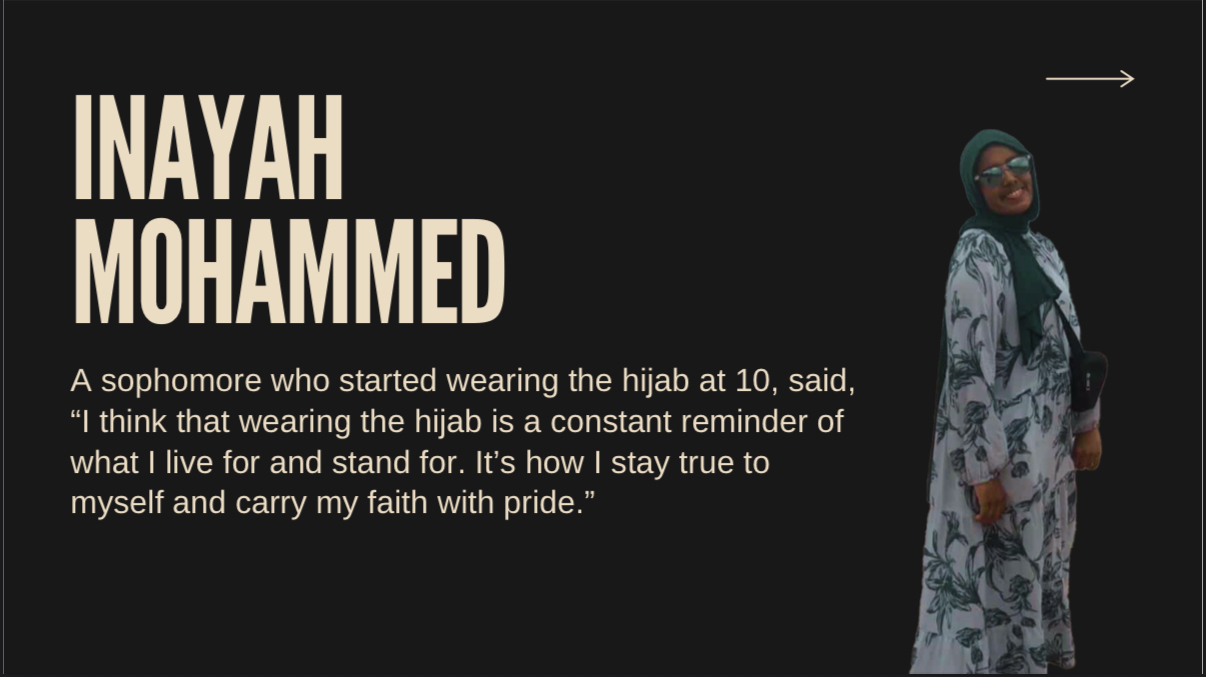

As part of this exploration, I spoke with several others whose experiences with hair reflect the power it holds in shaping personal identity. These individuals have not been featured in the story above, but their stories help complete the tapestry of diverse experiences.