You got a friend in me

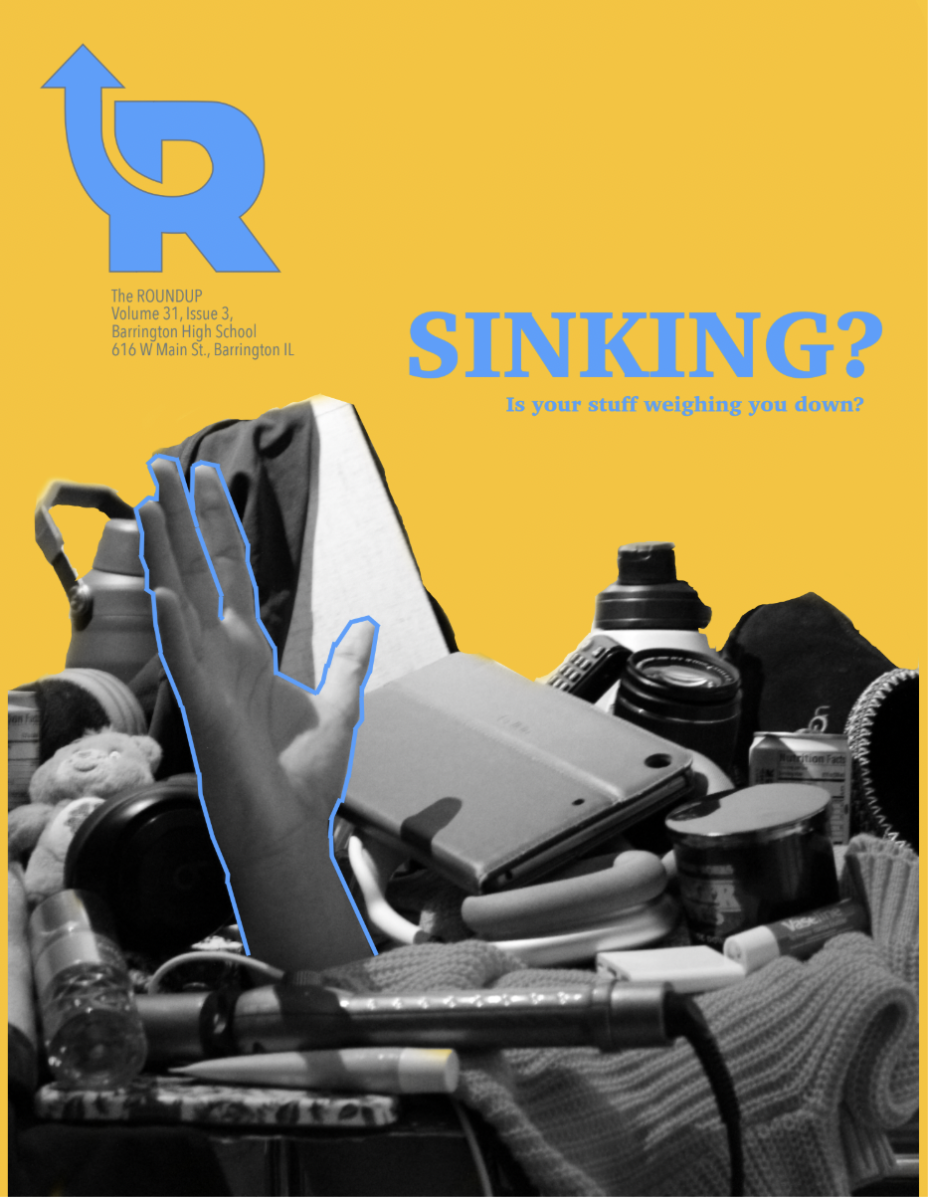

New school cop, Hakeem Smith, poses in front of his patrol car. Smith’s goal is to form a positive relationship with all students. Photo by Camille Wodarz.

Detective Hakeem Jamal Smith’s desktop is open to Pandora’s “Chill Pop” playlist. His office is one of stark contrast — on the walls hang inspirational quotes, and behind his desk sits a riot shield with “INTRUDER” taped to the back. As a resource officer, he has a job which mirrors that same dichotomy: a balance between guidance and reinforcement. Detective Smith wants to bridge that gap. The two, to him, don’t have to be mutually exclusive.

Smith was born on the south side of Chicago, made his way through high school and finished education with a degree in Sociology from Eastern Illinois University. From there, his path started turning.

“I worked for a gas company in Chicago… it was kind of fun, actually, shutting off peoples’ gas,” he said. “I had other part-time jobs, that kind of stuff. Worked as a Community Service officer for Morton Grove for a while, but eventually, I left there and went to the Cook County Sheriff’s Department as a Deputy for three years. I applied to Barrington [Police Department], and I’ve been here for two years, almost three. I just got promoted to Detective this May.”

Smith said coming to Barrington felt like a blessing. As he describes working in the Cook County County Correctional Facility (CCCF), the intense pressure and weight of his previous job became clear.

“I was just applying places… I knew I couldn’t stay in the Cook County PD,” he said. “The job changes you. You’re pretty much dealing with the worst of the worst… gangbangers, gang bosses, sex offenders… and all they’re given is four walls with a bed and a water fountain. It’s a very depressing place, to put it that way. So, therefore, you’re around so many people that have such negativity, you start becoming negative… in order to survive in a job like that, you would have to become cold and hard. You can’t show weakness, essentially.”

Detective Smith is none of those things. In conversation he is quiet, pausing often to think and respond — in speaking, the loudest voice is the radio chatter that occasionally fires off from his walkie-talkie. He patiently listens to the muffled conversation, then turns down the knob and places it back on his desk, softly continuing.

“I knew I wasn’t happy there, so I just applied everywhere — I didn’t think I’d get a job in Barrington,” Smith said. “But by the graces of God, I’m here.”

One specific instance stuck with Smith.

“[Working at the jail] was a foot in the door for law enforcement. One moment that sticks out to me was an administrative type situation: basically, there was a fight breaking out in the ‘open dorm’ setting. The open dorm is a giant room with seven hundred inmates in it — they have bunk beds, then come and go when they want. It was bedtime for them. A fight started, and I was the first officer to break it up — at the time, once I broke it up, my fellow officers didn’t say ‘good job’ or anything. They looked at me like ‘why did you jump in? Now we have to do paperwork,’ like it was a burden on them. The senior officer failed his job too. He wasn’t wearing his body camera, and so he blamed me for stopping the fight in the first place. I could have just backed off and waited, but me, I wanted to protect the inmates, and protect the people who I serve. It was one of those moments where I felt more disappointed in the job I had taken, and I wanted to put my efforts into making a difference somewhere else, rather than a place where they get mad at me for doing more than asked.”

In coming here, though, Smith has had a lot of opportunities to take what he learned from other departments (and not in the cold, hard, threatening way).

“Going from Cook County to Barrington is totally, totally different. Night and day. People are friendly here, people are happy… to go from a jail to a police department where I have a lot more freedom, just to be happy and find my career on my own instead of having to be what the sheriff wanted me to do is a total 360 for me. I’m so happy I have the opportunity to come here. From patrol to the school, it’s different, but it’s not that different. Like I said, people are happy, they’re social. I’m used to the big crowds, I know how to manage myself in a big school. A lot of my interactions were learned from Cook County, you’d find me having to interact with so many people at CC — I can use those skills [here], because there’s so many different personalities. I’ve learned the difficult people and now I can work with people who are easy to understand.”

Smith is aware that the kind of work that he came from might make a lot of students uncomfortable, and highlights other schools’ opinions on resource officers.

“I’ve heard of a lot worse,” he said. “Some schools have such bad issues, where there are schools that don’t want to give an officer an office. They feel as though an officer shouldn’t be in the school — which is 100 percent the principal’s decision. I don’t feel that at all in Barrington. 70 percent, definitely, are okay with the police and open with them. There’s still that 30, though, that just see the police as here to oppress and arrest. I want to reach that 30 and show that there’s way more an officer can do.”

According to the National Association of School Resource Officers, there are roughly 17,000 resource officers in the country. That’s out of roughly 25,000 high schools; the number is growing, though, as threats to student security make the position a necessity in the eyes of more and more schools. However, as skepticism of police grows, the position is questioned — especially by youth. In a recent survey by Gallup, only 50 percent of 18-29-year-olds trust the police, down from 57 percent three years prior. Smith understands this, though. In reaching to the students, he said he has a lot of concepts and ideas that focus on tricky conversations that might need to be had, both at school and at home.

“Well, this summer, I was really trying to get programs started in the high school that have to deal with sex violence awareness,” he said. “I didn’t have enough time, it’s just so much research, so many people I need… hopefully next year. If I can’t, I want to work with different organizations to make open mic nights where people talk about uncomfortable conversations. I find that a lot of the issues we have nowadays are because people don’t wanna have that awkward conversation. People take conversations that are that uncomfortable and make negative situations of them — I feel as though people need to take sex violence or inappropriate drug use and move them into a situation that they learn from it, not just look past it.”

Detective Smith imparts, above all, that the future is important. Going forward, he wants to instill a feeling of trust and genuine security around campus.

“I want students to know and understand that I’m a very approachable guy,” he said. “I might be big and burly, but I’m not a person that wants to get anyone in trouble — if I have to do my job, I have to do it. But if there’s a situation where I can just be a good guy, guide them to resolving an issue while getting no one in trouble, I’d prefer to do that. I don’t like to police 100 percent. I want to be a leader and for people to see me as approachable. I want to make this school year one where everyone can get to know me and I can get to know them. I don’t want a situation where I just sit in my office. If they see me walking in the hall, feel free to say hi because it will make my job easier and the year better. That kind of student interaction and help can make this a proper place to be.”

Your donation will support the student journalists at Barrington High School! Your contribution will allow us to produce our publication and cover our annual website hosting costs.